Ringneck Snake: (Diadophis punctatus)

Uploaded on April 15, 2008 James Harding  (photographer, copyright holder, identification), Michigan State University

(photographer, copyright holder, identification), Michigan State University

by Ted Bell

Taxonomy:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Class: Reptilia

Order: Squamata

Suborder: Serpentes

Family: Colubridae

Genus: Diadophis

Species: punctatus

Indentification:

Length25.50 to 46 cm

(10.04 to 18.11 in)

The ringneck snake is typically a slender olive, brownish, blue-gray, or black snake on top and can vary with cream and orange-reddish color on the posterior. This difference in coloration can vary among subspecies. The most defining characteristic is its conspicuous yellow, orange, or cream neck band (neck bands are absent in some populations like in southern New Mexico and Utah). The ring may be interrupted or, in the cases of the regal ringneck snakes (D. punctatus regalis) and key ringneck snakes D. punctatus acricus, may appear only as a trace or be completely absent. The abdomen is orange-yellow, but western and extreme southern subspecies show a change in color to orange-red toward the posterior. The presence and configuration of black spots on the abdomen can be used to distinguish subspecies. (Conant and Collins, 1998)

Eastern subspecies have 15 scale rows at the anterior end; western subspecies have 17. Scales are smooth and the anal plate is divided. The species has a length of 25 to 38 cm, except D. punctatus regalis, which measures 38 to 46 cm. Newborn snakes have the same markings and coloration as adults. Generally speaking, adult females are longer than adult males. Molting occurs in all months of the year. (Blanchard, 1942; Conant and Collins, 1998; Myers, 1965)

Similar Species: 1) Black-headed snakes (Tantilla species) usually have whitish or beige neckband, and lack black spots on the belly; reddish color on the belly is bordered on each side by pale gray, and there is no loreal scale. 2) also the sharp-tailed snake (Contia tenuis).

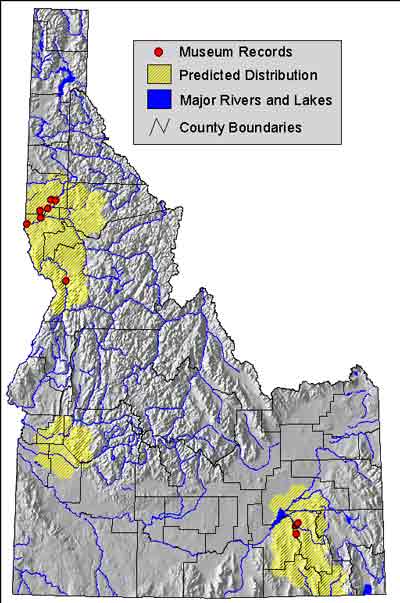

Distribution:

The ringneck snake has a very wide distribution in the United States and are very common throughout eastern and central North America. Their range extends from Nova Scotia, southern Quebec, and Ontario to south-central Mexico. They also cover the entire eastern seaboard except for areas along the gulf coasts of south Texas and northeast Mexico. The range extends laterally to the Pacific coast except for large areas in drier regions of the western United States and Mexico.

http://www.natureserve.org/explorer/servlet/NatureServe?searchName=Diadophis+punctatus+

Distribution map of Idaho

Figure 1: Distribution of Ringneck Snakes in Idaho

http://imnh.isu.edu/digitalatlas/bio/reptile/serp/dipu/dipumap.htm

Habitat:

Ringneck snakes are abundant were there are ample hiding places but they can inhabit almost any environment. They prefer moist environments/habitats around 27 to 29 degrees Celsius like woodlands, forests, grasslands, chaparrals, farms, and gardens. Northern and western subspecies prefer coverage under stones or under the loose bark of dead trees, and are often found in open woodlands near rocky hillsides. Southern subspecies tend to stay in conspicuously wet locales, such as swamps, damp forests, or riparian woodlands. (Ditmars, 1930; Dundee and Miller III, 1968)

Behavior:

Ringneck snakes are only active during the night time hours. However, individuals can sometimes be found basking or warming themselves during daylight hours, usually under or around rocks directly exposed to the sun in open wooded areas. Also ringneck snakes perennially return to single denning sites. Ringneck snakes are very secretive, non-aggressive species that are nocturnal and rarely exposes itself to daylight. Despite their secretiveness, however, ringneck snakes are social animals and many populations exist as large colonies, numbering 100 individuals or more. Communities of six or more may be found sharing a single microhabitat. No information is known on the hierarchical structure of ringneck snake colonies. (Blanchard, 1942; Blanchard, Gilreath, and Blanchard, 1979; Dundee and Miller III, 1968)

Prey: Ringneck snakes prey on small salamanders, lizards, frogs, earthworms, and other juvenile snakes. They dont have a particular favorite prey, they prey on whats most abundant. Ringneck snakes also can use partial constriction to subdue their prey.

Predation: Ringneck snakes are prey for coral snakes (Micruroides euryxanthus), kingsnakes (Lampropeltis spp.), racers (Coluber constrictor), and other snakes that inhabit the same habitat as the ringneck snake. Ringneck snakes are also prey for wild hogs, opossums, shrews, armadillos, skunks, screech owls, and bullfrogs. Large spiders and centipedes have also been seen feeding on small or juvenile ringneck snakes.

Defence: When startled ringneck snakes coiler their tails and raise it toward the intruder(s). This behavior occurs in regions were populations have orange-red under belly colorations. Ringneck snakes also emit a musky saliva that is secreted from the corners of its mouth and can have a lasting, pungent, clinging odor.

Reproduction:

Breeding interval

Ringneck snakes breed once each year.

Breeding season

Ringneck snakes breed in the spring or fall.

Number of offspring

3 to 10

Age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

3 years (average)

Age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

3 years (average)

Female ringneck snakes release pheromones through their skin to attract males during mating season. During mating males rub their closed mouths on their mates's body. Then he bites the female around her neck ring, and aligns his body with the females to release his sperm.

Mating of ringneck snakes can occur in spring or fall--delayed fertilization is possible--and eggs are laid in June or early July. Females lay eggs each year, 3 to 10 eggs can be laid at one time, and are deposited together in covered, moist locations. In areas where colonies exist, it is not uncommon to find eggs laid in communal nests. A single egg is white with yellow ends and is elongated, approximating 1 inch in length. Juveniles hatch in August or September. (Aardema et al., 2004; Blanchard, 1942; Jackson and Mirick, 2000; Myers, 1965)

Reproductive maturity of both sexes is reached at the age of three years, that is, by their fourth summer. Male ringneck snakes mature at a smaller size than females do. (Blanchard, 1942; Blanchard, Gilreath, and Blanchard, 1979)

Ringneck snake eggs are not cared for, there is no parental investment after choosing a nest site and laying the eggs. This largely contributes to the high mortality rate of young ringneck snakes. (Dundee and Miller III, 1968; Scott, 1996)

Scientific Study:

The Department of Biology at University of Southwestern Louisiana, Lafayette, LA. conducted a scientific study on ringneck snakes to see if they can detect substrate odors originating from its prey, a territorial salamander (Plethodon cinereus). They conducted two experiments to determine (1) if substances from the salamanders body and tail are equally attractive to the ringneck snake and (2) whether individuals of ringneck snakes responed the same to these salamanders with tails and without tails. They used red-backed salamanders (Plethodon cinereus) because in northern Michigan ringneck snakes primarily feed on these salamanders.

Background of Snakes: "In some squamate reptiles, the role of chemoreception has been investigated in the detection and identification of integumental cues or other substances derived directly from the potential prey (reviewed in Halpern, 1992)". Snakes possess well developed olfactory systems as well as accessory olfactory systems that they use in locating and catching prey.

Experiment 1: Salamander Odors as Potential Chemoattractants: They specifically tested the following hypotheses, "(1) Individuals of D. punctatus will direct significantly more tongue flicks toward odors originating from the ventral surface of the tail and the body of P. cinereus than from the ventral surface of a non-prey species (crickets)(Lancaster and Wise, 1996)." They predicted that the ringneck snake would respond to the prey species odor better than they would to the non-prey species odor. "(2) Ringneck snakes will exhibit significantly different numbers of tongue flicks in response to odors originating from the tail versus the body of P. cinereus. No direction for the response by snakes to these two odor sources was predicted (Lancaster and Wise, 1996)."

Methods: They presented odors to snakes on cotton swabs, one swab had the odor of the salamanders body, one swab had the odor of the salamanders tail, and the last swab had the odor of the cricket. They observed the number of tongue flicks to odor sources over a period of 60 seconds beginning with the first tongue flick (rate of tongue flicking, RTF) and the period of time prior to the first tongue flick (LATENCY). They obtained the odors by rubbing a cotton swab (moistened by distilled water) over a small area on the ventral surface of the animals. For the tail they rubbed a swab on the posterior end of the cloaca.

Results: They found no significant correlations between RTF and LATENCY for responses to odors from bodies, tails, or crickets. However, they did find that swabs with tail odors had a higher RTF then any of the other swabs.

Experiment 2: The second experiment was to see if responses differed with odors from tailed or tailless salamanders. They looked at (1) tailed salamanders versus tailless salamanders, (2) tailed salamanders versus the control, and (3) tailless salamanders versus the control. They predicted that behaviors would increase with odors from (1) tailed versus tailless (tail-autotomized) salamanders, (2) tailed salamanders versus the control, and (3) tailless salamanders versus the control.

Methods: They tested the behavioral reponses of ringneck snakes to the substrate odors of tailed and tailless salamanders and a non-prey dipteran species (D. virilis) in a chamber resembling an open Y-maze. They placed 36 pieces of damp filter paper with the odor of the control randomly on one side of the chamber and did the same for the talied or tailless filter papers on the other side of the chamber. (1) with substrate odors on the filter paper from a tailed individual of P. cinereus on one side and odors from D. virilis on the other side of the chamber and (2) with substrate odors on the filter paper from a tailless individual of P. cinereus on one side and odors from D. virilis on the other side of the chamber. They put the snake in the end of the shaft of the Y-maze and closed it off. Each snake was tested twice randomly. They monitored the snakes activities for 30 min and recorded the amount of time the snakes spent on each side (SIDE), and the time spent on the NON-EDGE sides.

Results: They found no significant correlations were found between RTF and NON-EDGE, RTF and SIDE, or SIDE and NON-EDGE for snakes paired with tailed and tailless salamanders. They did also find that snakes spent more time on the side of the chamber with tailed odor then the control odor. However, there was no difference with tailless and control.

Discussion: Their study demonstrates that snake predators can recognize prey and distinguish between substances derived from different anatomical areas of their salamander prey. "The red-backed salamander is able to autotomize its tail as an antipredator defense against snake attack (e.g., S. J. Ar- nold, 1982). Based on our results, the tail, perse, elicits greater chemosensory investigation by the salamanders' natural predator, D. punctatus, than does the body. Thus, tailed salamanders may increase their chances of survival when encountering predators by diverting attacks to the expendable tail using attractive chemical cues. Conversely, tailless salamanders cannot use autotomy as an escape mechanism and may have decreased survivorship compared to tailed salamanders when attacked by a predator (S. J. Arnold, 1982). However, if predators are attracted to odors produced in the integument of the tail, then the absence of the tail may confer an advantage to tailless salamanders by reducing their likelihood of being detected in the first place. Thus, tailed salamanders may be better able to defend themselves during encounters with predators, but tailless salamanders may be encountered less frequently by predators that use chemical signals from the tail in the detection and identification of prey (Lancaster and Wise, 1996)."

References:

Cossel, John. Diadophis punctatus. Digital Atlas of Idaho. 1997. http://imnh.isu.edu/digitalatlas/bio/reptile/serp/dipu/dipu.htm.

Lancaster, D. L., and S. E. Wise. 1996. Differential Response by the Ringneck Snake, Diadophis punctatus, to Odors of Tail-Autotomizing Prey. Herpetologica 52: 98-108.

NatureServe. 2008. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.0. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed: October 1, 2008 ).

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. Western Reptiles and Amphibians. Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, New York, USA.

Yung, J. 2000. "Diadophis punctatus" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed October 02, 2008 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Diadophis_punctatus.html.

Created By: Tim Powell

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.